If someone asks you to write a big check, but they add, “I’ll give you the money back in five years, but you cannot collect until then,” would you do the deal? That’s not a small ask. Some investors would demand compensation for using your capital. Now, imagine you had to wait 10 years. Would you ask for the same terms as if it were five? The above scenario is what private investing is all about—and it all boils down to something called the illiquidity premium.

Unlike publicly-traded stocks or bonds, private deals require you trade access to your capital for the potential to earn a higher return. This trade-off is one that many investors have increasingly gravitated toward over the last 10 years. Consulting firm McKinsey & Company estimates that private market assets under management (AUM) grew by $4 trillion over the past decade, a 170% increase, including a 10% increase in AUM in 2019 alone.

What is the

illiquidity premium?

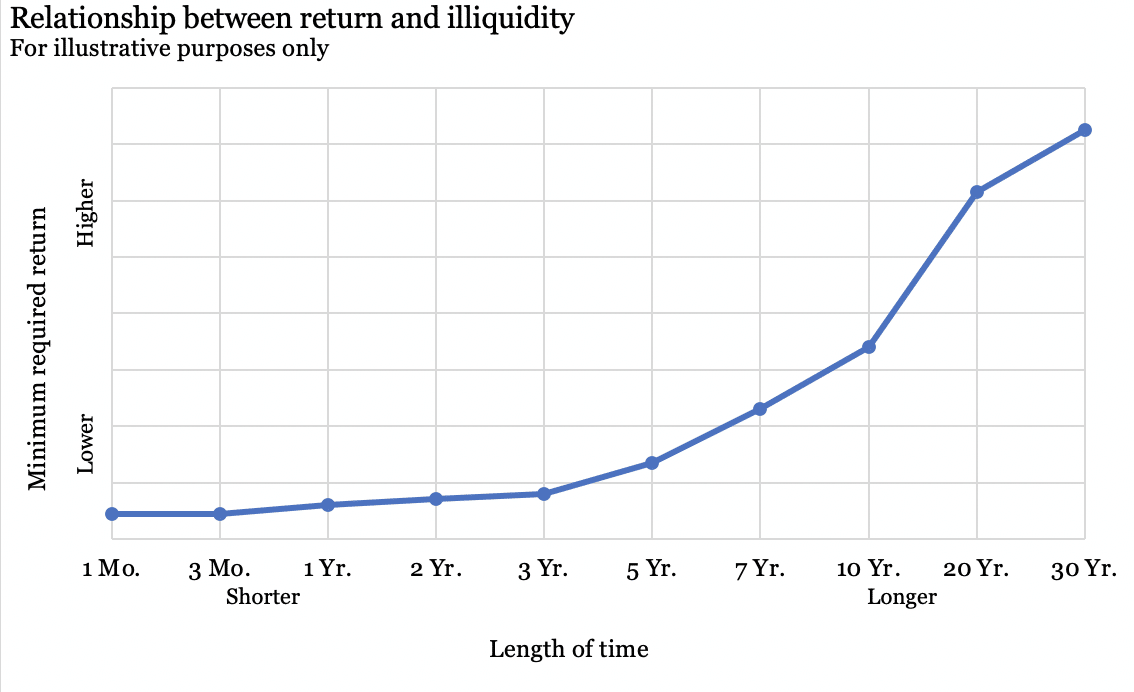

The illiquidity premium is the compensation investors demand in exchange for losing access to their capital. Basically, the longer an investor must wait to recover their principal, the higher return they can demand. This relationship between time and return is central to investing in private real estate. Why? Because commercial real estate projects take time to develop and sell, making them harder to trade, like stock market securities.

Risk is another critical factor to determine the minimum return you should expect from an illiquid investment. For example, consider two projects that take five years to complete. Suppose one is a ground-up development, while the other is a total renovation job: you may demand a higher return from the renovation job than the ground-up project because it could carry more risk.

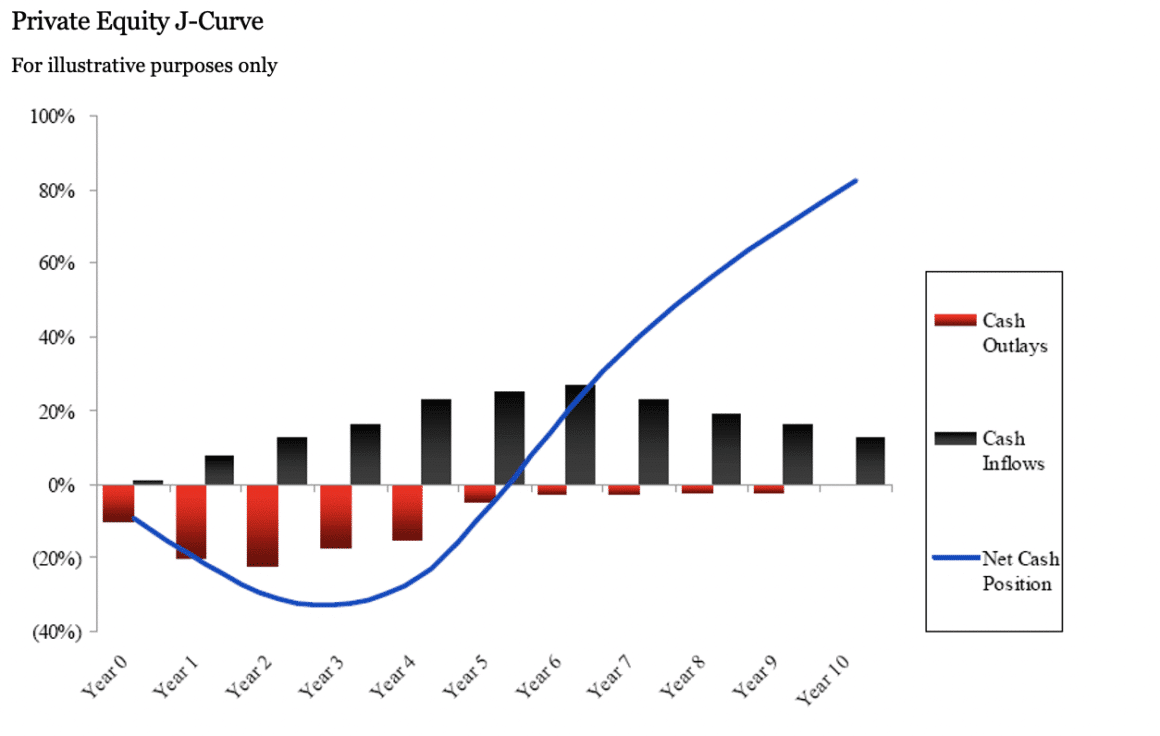

The illiquidity premium — the amount you should demand in exchange for losing access to your principal — depends on the specific deal. That said, we can put some definition around the deal by understanding the project’s expected J-curve and the general risk/reward category. Then, you can judge the expected returns relative to the risk to make an informed decision.

Understanding the J-curve

Private deals follow what’s known as a J-curve. A J-curve traces the initial capital outlay’s investment path, past the break-even point, before ending with (hopefully) positive cash flow and an increase in market value. “J Curve” is the visual representation of the aphorism “you need to spend money to make money.”

In the example above, it takes about five years to hit the break-even point. During that time, the manager uses investor capital to acquire, renovate, build, or otherwise improve a given property or parcel of land. After that, the property resumes cash-flowing. As profits accumulate, distributions back to investors increase before the deal finally concludes, and investors receive their capital back.

Famously, Blackstone spent billions of dollars gobbling up distressed single-family homes across the United States in 2011, when home prices hit their nadir following 2008’s global financial crisis. They spent the next few years renovating their giant portfolio of homes before repackaging them into single-family rental properties. Their investors received cash flow from rents before selling the portfolio off in 2019 for a tidy profit.

The amount of time your capital is in use depends on each deal. Fix-and-flip deals can be as quick as much 18 months, whereas ground-up development can take 10 years or more. It would be best to plan for your capital to be illiquid for a minimum of five years. If that amount of time creates issues in your retirement plan or your current cash flow, then you may want to consider a more liquid investment.

Different Private Real Estate Risk/Return Categories

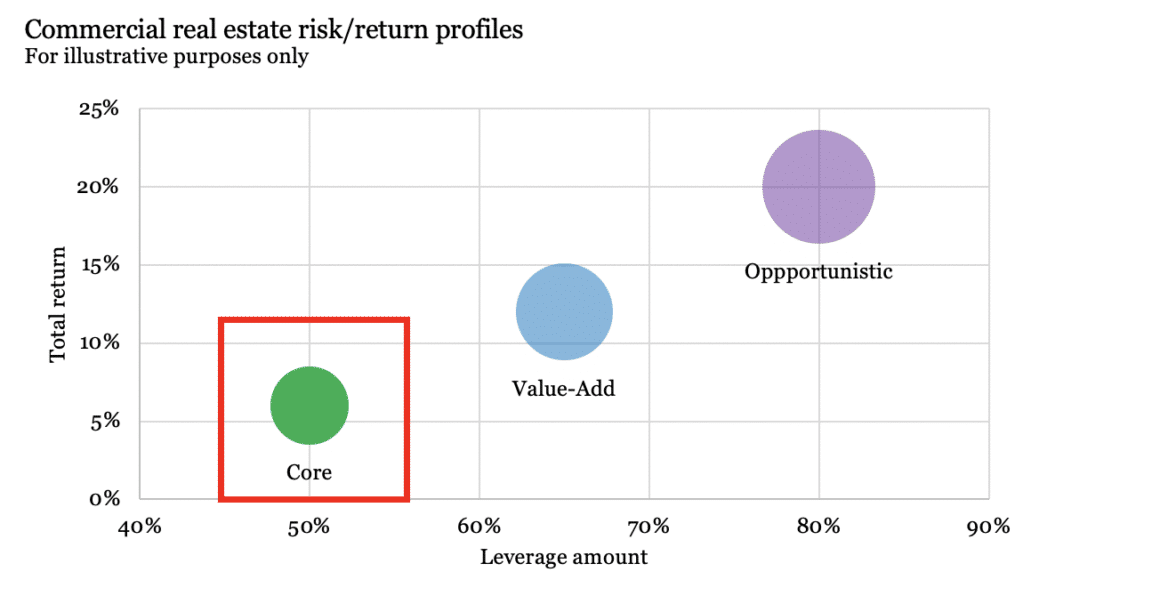

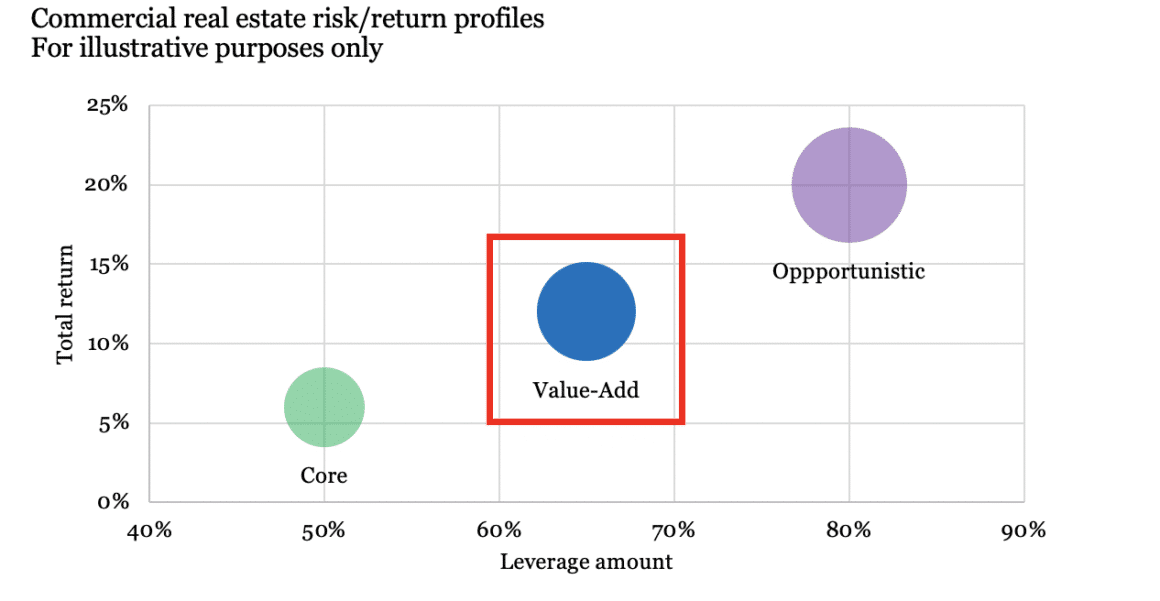

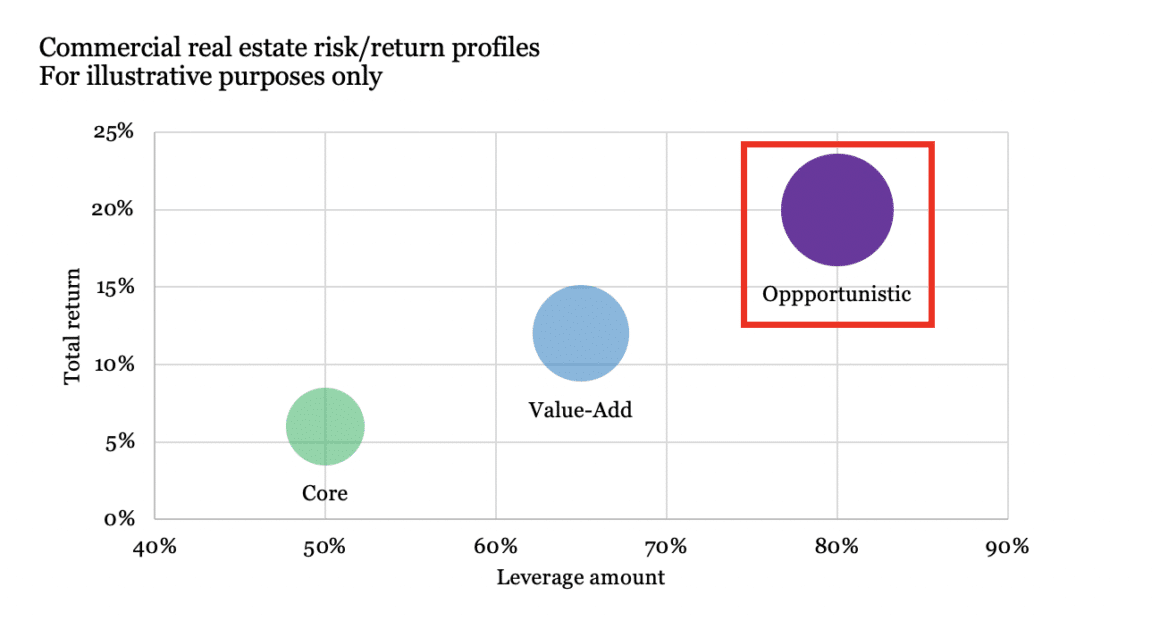

There are three general risk/reward levels in commercial real estate: core, core-plus, value-add and opportunistic. These three broad categories bucket investments based on the project’s scope, risk, timeline and, most importantly, expected returns.

Core/core-plus: These are commercial real estate properties that are already built and are currently cash-flowing. Current income provides 70-80% of the return, with a potential total return between 6-8% per year. The properties are well-capitalized with low leverage amounts, typically between 30-50%. As a result, core or core-plus properties are considered the lowest risk category. Depending on where your principal sits in the capital stack, you could have significantly higher liquidity in a core deal than the other risk/return categories. However, the trade-off to all this safety is that core properties rarely see much appreciation in value above the general market.

Value-add: As the name suggests, these are existing properties that need improvements to bring them back up to market value. Generally, these are core properties that haven’t been as well maintained but are still structurally sound. That HGTV show “Fixer-Upper” is value-add in action: the worst house in the best neighborhood. All renovation projects carry risk, so it’s essential to clearly understand what the manager’s improvement plan is for the property. Value-add projects take time and typically involve more leverage, but, despite those added risks, you can potentially realize returns of 13-18% annually, depending on the deal.

Opportunistic: These projects take the longest, carry the most risk, but can generate outstanding returns — 20% or more per year. Expect your principal to be unavailable for 10 years, and the returns to resemble the J-curve illustrated above. Ground-up development or redevelopment (tear-down jobs, basically) are typical opportunistic projects.

While there are often significant risks along the way, opportunistic projects can offer long-term investors the chance to own a core property. The most straightforward example of this transformation is a new sports and entertainment venue. The team and city are betting that, despite the high costs of building a new stadium, the finished stadium will encourage other development around it to create multiple sources of year-round revenue. What may have started as a reclamation project or a patch of dirt is now a hub of economic activity 10 years later.

Conclusions about the illiquidity premium

Conceptually, the illiquidity premium gives us a framework to weigh up access to capital, risk, and the potential return for any given project. If a project has a long timeline, that typically means it’s a riskier value-add or opportunistic project. Therefore, investors should demand a higher rate of return for shouldering the additional risk. Conversely, projects with shorter timelines typically mean less risky projects on existing structures. This means investors should expect a lower return rate for taking less risk. In general, investors in any private project should expect their capital to be under contract for a minimum of five years. Hopefully, understanding more about the illiquidity premium can help clarify the exchange you make when you invest in private real estate. Fortunately, the fundamentals and asset flow from investors of all sizes strongly suggest that private real estate has a significant role in any investor’s asset allocation.

About caliber

Caliber provides alternative access to individual and institutional investors via well-structured, private equity real estate investments in projects that we either develop or manage or both.

To invest in real estate and learn more, contact us today.